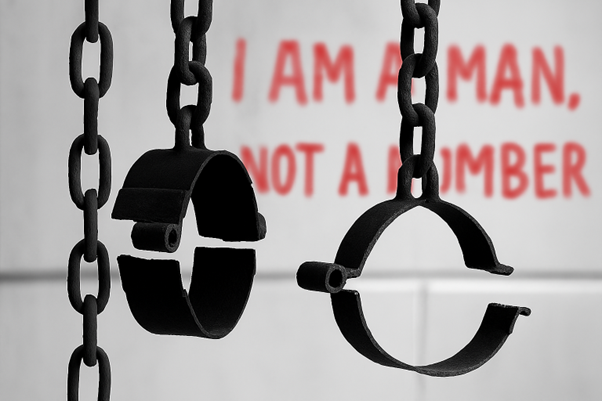

Paul and Silas standing up against slavery.

One day, as we were going to the place of prayer, we met a slave-girl who had a spirit of divination and brought her owners a great deal of money by fortune-telling. While she followed Paul and us, she would cry out, ‘These men are slaves of the Most High God, who proclaim to you a way of salvation.’ She kept doing this for many days. But Paul, very much annoyed, turned and said to the spirit, ‘I order you in the name of Jesus Christ to come out of her.’ And it came out that very hour.

But when her owners saw that their hope of making money was gone, they seized Paul and Silas and dragged them into the marketplace before the authorities.

They said to the Magistrates, ‘These men are disturbing our city; they are Jews and are advocating customs that are not lawful for us as Romans to adopt or observe.’ The crowd joined in attacking them, and the magistrates ordered them to be stripped of their clothing and beaten with rods. After they had given them a severe flogging, they threw them into prison and ordered the jailer to keep them securely. Following these instructions, he put them in the innermost cell and fastened their feet in the stocks.

About midnight Paul and Silas were praying and singing hymns to God, and the prisoners were listening to them. Suddenly, there was an earthquake, so violent that the foundations of the prison shook; and immediately all the doors opened and everyone’s chains fell off.

Acts 16.16-26

Luke describes the fortune-teller girl in the Roman colony of Philippi as a slave.

We react in a curious way to the word slave in this country, in this age. For instance, my grammar checker (which doubles up as a puritanical political correctness superintendent) throws a hissy fit when I use the word. But I can’t help it. I don’t want to soften the harsh impact, and if the word slave offends, then so be it.

Slavery: Not Just History

In Britain, the word slave often evokes our colonial past. Think of Liverpool and Bristol’s role in the transatlantic slave trade. Next, think of how, even after abolition, slavery effectively persisted in America, especially in the South, where Black people remained disenfranchised and exploited. Finally, (to the church’s shame), think of how scripture was misused to justify it.

But slavery is not just a historical stain. It’s a present reality.

According to the Global Slavery Index, over 50 million people are enslaved worldwide, right now. Slavery includes any situation where a person is forced into an economic arrangement against their will and lacks control over their own destiny.

This includes forced marriages, often affecting women in South Asia. (Note, though, that an arranged marriage is not the same thing as a forced marriage.) While many arranged marriages are consensual and fulfilling, some become coercive, stripping individuals of bodily autonomy and economic freedom. In such cases, sexual acts become rape, and domestic labour becomes slavery.

It also includes child conscription into armed militias—especially in countries like Eritrea, where an estimated 10% of the population lives in conditions of forced labour.

Extremist groups like Boko Haram and ISIS declared slavery to be a legitimate part of jihad. The legacy of ISIS lingers, even though it has been largely defeated. Thus, for instance, in Syria, over 136,000 people remain enslaved. Although that’s a reduction from previous years, it’s still appalling.

Slavery: Not Just “Their” Problem

It’s tempting to view slavery as a foreign issue. But it’s not.

Over 4 million slaves live in Western democracies. Disturbingly, that includes the USA, Germany, France, Italy, and the UK. Human trafficking is the second most profitable criminal industry globally, just behind drug smuggling. Do you believe the rhetoric that the small boats and the so-called migrant crisis is just selfish foreigners coming over here to steal our jobs and overpopulate our crowded islands? You’re wrong: it’s deeply entangled with trafficking networks.

People want freedom from poverty, abuse, and war. They want to be free from gender inequalities and discrimination. Everyone wants opportunities for a better life. They want all the things that you want. So traffickers deceive them, making promises they have no intention of fulfilling before transporting them (often—cruelly—at the victim’s expense) and then enslaving them to meet a demand for cheap labour in developed nations. And the victims will remain slaves until they have paid the debts incurred in the transportation, which they can never do because the interest rates outstrip the meagre income.

Slavery also hides in plain sight. Fuel poverty, predatory lending, and exploitative wages trap people in cycles of dependence. If you rely on food banks to survive, are you truly free?

Slavery is not an overseas problem, and it is not a historic problem.

Legal Slavery and Economic Pushback

Paul and Silas’ treatment in Acts shows that freeing the enslaved often provokes backlash. The girl in Philippi was doubly imprisoned—by a spirit and by profiteers. When Paul and Silas freed her, her owners were furious. The Apostles had interfered with their economic interests. The Christians had prevented them from exploiting the girl for their own income.

But slavery is not a historic problem, and it is not an overseas problem. It still happens here, and it is still happening now, but there will be pushback if we try to free the enslaved.

Take gambling. Slot machines are legal, yet they exploit vulnerable people. However, if Christians campaign to remove them, those profiting from the industry will resist.

Or alcohol. While moderate drinking is harmless for many, the industry profits most from excess. I’ve worked in the wine trade. I heard, firsthand, managers disparaging moderation. Campaigning against alcohol addiction invites pushback from those who benefit financially.

I’m afraid that even the law-abiding community is not always thrilled to have ‘religious folk’ interfering.

Let me be clear: I’m not advocating the abolition of alcohol or gambling. Prohibition drives problems underground. Most people who drink or gamble do so responsibly. So what we need are mechanisms to free those who aren’t free from such addictions. Freeing those enslaved people threatens vested interests.

The Cost of Speaking Out

Standing against slavery, whether economic, spiritual, or systemic, comes at a cost. So Paul and Silas were beaten and imprisoned for freeing a single slave girl. Good people often suffer for doing good things.

As Paul wrote in 2 Corinthians 11:23–27, he endured countless beatings and imprisonments for the sake of Christ. He was motivated by the message, not daunted by detractors.

We, too, will face resistance. We will get it from both the corrupt and the law-abiding. But as Edmund Burke famously said:

“All that is necessary for evil to triumph is for good men to do nothing.”

Singing in Prison: A Theology of Freedom

Paul and Silas sang in prison. Were they idiots, or people of faith?

Their worship echoed the Spirituals sung by enslaved African Americans—songs of hope, defiance, and spiritual freedom. Their singing proclaimed a truth:

Freedom is not just circumstantial. It’s spiritual.

When people enter into a relationship with God, remarkable things happen.

- Fortune-telling girls are freed.

- Drug addicts find relief.

- Alcoholics recover.

- Prostitutes find the courage to seek help.

I wish I could say the same for all sex slaves and trafficked workers. I wish I could say the same for all asylum seekers and child soldiers. And I wish I could say the same for all addicts. But the Holy Spirit can reach their hearts, even if their bodies remain ensnared by evil.

That’s where we come in.

We are Christ’s body—his hands and feet on earth. God calls us not to “do nothing”. God calls us to do something. To release the captives. To set the oppressed free.

God calls us to rise to that call.

Let’s be agents of freedom.

May all God’s children be genuinely free.

Scripture quotations are adapted from the New Revised Standard Version Bible, copyright © 1989 National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide.